Aesthetic Theory, Abstract Art, and Lawrence Carroll by David Carrier

Author:David Carrier

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Bloomsbury UK

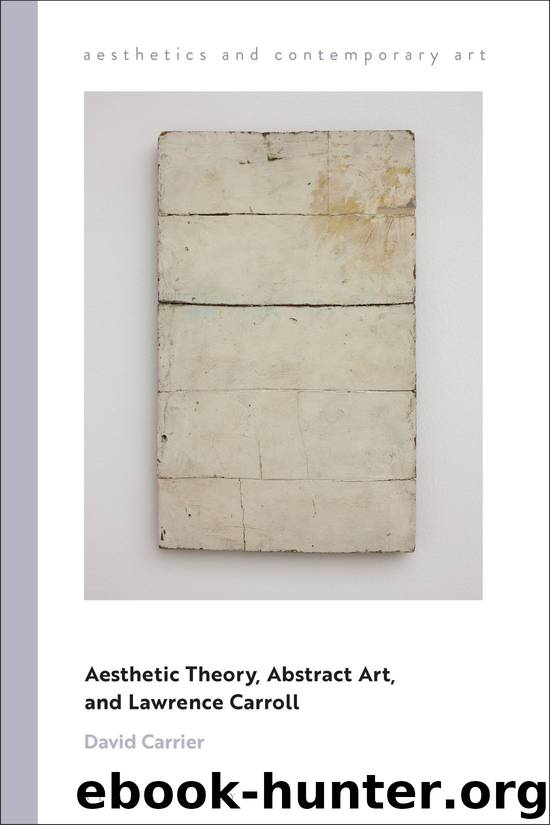

Figure 8 Untitled, Insert Painting (1985).

Let’s start our discussion by looking at titles of artworks, for often titles of abstractions are revealing. Almost inevitably identifying the subject matter of figurative painting provides its title—landscape, nude, cityscape. With abstractions, however, some artists feel that giving titles is a reductive procedure. And so they prefer to number their pictures—David Reed and Thomas Nozkowski do this, and so does Gerhard Richter. Sean Scully always titles his paintings. His titles, names of friends, books, and places of importance offer significant interpretative clues. And Cy Twombly’s titles often display his erudition; for example, Triumph of Galatea (1961), Empire of Flora (1961), and Hero and Leander (1981). You see his love of classical Roman literature. Contrast Carroll’s titles from the Ligornetto exhibition—keeping in mind that many of his works are untitled. There are straightforward references to pop culture—Yellow to Yellow for Neil Young; literal descriptions of the works—Bucket, which is one; Small Figment, which is not especially small; and Figment, which is larger; and Untitled-Flower Painting #2 and Untitled (Stacked Painting), which are paintings with flowers and, in the second case, a stacked painting. No classical culture here! Look at Carroll’s list of what a painting can do: “It could sleep, shed its skin, sit on the floor, breathe, repair itself, lean, empty itself, rest in a corner, fold over on itself, be pieced back together, survive, be optimistic, hope, sweat. I began to explore these possibilities in my work, and to trust in them” (Carroll qtd Milazzo 1998: 42). As his titles signal, his ways of visual thinking are very literal-minded.

In the 1970s, David Reed was making process art. In a recent retrospective with a marvelously evocative title “Painting Paintings,” which is devoted to these early works, the curator Katy Siegel meticulously reconstructs his art world life during this period. “The problem . . . was that process inevitably became image. In the end, illusion crept in; value contrast and the very fact of the picture plane created a picture. More disturbing still was Reed’s feeling that even as he made a work, he was outside the painting as well as inside it” (Siegel and Wool 2017: 6). His #73 (1975), which was in that exhibition, consists of thirteen horizontal stripes, on a canvas just over six feet tall, these paint lines running more or less straight, as if Reed isolated for display the gestural brushwork of the abstract expressionists. What’s perhaps problematic is that these early Reeds appear less finished pictures than (very handsome!) samples of his activity of art making.

Given these obvious uncertainties, it’s not surprising that he soon moved on, both in his painting and in his theorizing about it. Reed related his 1980s abstractions to baroque painting. Comparing Guercino’s Samson Captured by the Philistines (1619), which is in the Metropolitan, to his works, he suggested: “I can’t use the religious light of baroque painting, which comes from above, from God. Instead, I can use another kind of divine light, techno-light, which is uniform and has no source” (qtd Paparoni 1993: 133).

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Art of Boudoir Photography: How to Create Stunning Photographs of Women by Christa Meola(18603)

Red Sparrow by Jason Matthews(5450)

Harry Potter 02 & The Chamber Of Secrets (Illustrated) by J.K. Rowling(3657)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(3524)

Drawing Cutting Edge Anatomy by Christopher Hart(3508)

Figure Drawing for Artists by Steve Huston(3429)

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (Book 3) by J. K. Rowling(3337)

The Daily Stoic by Holiday Ryan & Hanselman Stephen(3287)

Japanese Design by Patricia J. Graham(3152)

The Roots of Romanticism (Second Edition) by Berlin Isaiah Hardy Henry Gray John(2900)

Make Comics Like the Pros by Greg Pak(2898)

Stacked Decks by The Rotenberg Collection(2866)

Draw-A-Saurus by James Silvani(2701)

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (7) by J.K. Rowling(2701)

Tattoo Art by Doralba Picerno(2645)

On Photography by Susan Sontag(2620)

Churchill by Paul Johnson(2565)

The Daily Stoic by Ryan Holiday & Stephen Hanselman(2561)

Drawing and Painting Birds by Tim Wootton(2491)